On the trail of the Tiger

Saturday 6th August 2005

The last two weeks in Sumatra have been exhausting but exhilarating. We left Jakarta early one morning, accompanied by Pak Wald and Pak Daniel of the Sumatran Tiger Conservation Program, and began a four-day journey up impossibly bumpy roads to the forests of central Sumatra. En route we took in a ferry journey passing Krakatoa in the distance, stopped over at the elephant training centre in Way Kambas, and passed through the concrete skyscrapers that dominate the villages where bird’s nest soup is the primary industry. After three days circumnavigating the many potholes of the trans-Sumatran highway, we eventually arrived at the office of the STCP. That evening we were introduced to the rest of the team and were shown a small sample of the thousands of photos they have collected from their camera traps in the forests, including tapir, clouded leopards, porcupines, deer, elephants, and, of course, tigers. Pak Wald and Pak Yunus, the STCP field manager, then showed us some of the STCP’s recent confiscations – tiger and leopard skins, bones, and teeth.

The next day we traveled to some of the palm oil plantations that surround the borders of the forest where the STCP’s Tiger Protection Units run their patrols. Approaching one plantation we managed to get some shots of a huge illegal saw mill just off the road, and talked to a rubber-tapper and his family whose livelihood is threatened by the continuous expansion of palm oil monoculture. Arriving at another plantation still being established nearby, Pak Wald was shocked to find how quickly the forest had been cleared – the area had still been forest when he had last visited, just weeks earlier. On our way out of this plantation we encountered two workers carrying an Argus Pheasant that they had recently captured on the outskirts of the plantation. The Great Argus is a CITES Appendix-I listed endangered species. The unfortunate bird we met had its eyes stitched closed to “keep it calm”. The workers expected to make around £14.50 from selling it. We resisted the temptation to buy this bird from them in order to set it free – our doing so would only mean that word would get round that foreigners were paying for animals and would compound the problem.

Later, in yet another plantation, we came across a baby macaque being kept as a family pet and tethered by the neck on an extremely short rope. It is likely the macaque faces a bleak future – a macaque is almost certain to be killed by others in the group if released into a wild population. It felt like every way we turned there were animals that faced similarly uncertain futures as their forest disappears to make way for palm oil.

The next couple of days were spent more happily. We traveled to the STCP base within the forest borders and from there we were able to film siamang whooping through the treetops, and witness the spectacular site of hornbills swooshing and honking overhead. We spent a couple of days trekking the jungle trails with the team, filming the set up of the camera traps and looking for snares set by poachers. We were lucky enough to come across some tiger prints, including some left fairly recently by a tigress and her cubs.

Members of the tiger team are recruited only after rigorous jungle training, and although by now fairly acclimatized to the 33 plus degree heat, we found it hard to keep up with the speed with which they move through the forest. They decided we looked like Ninja Turtles due to the big camera cases we were heaving around on our backs, and I think that our obvious discomfort kept them entertained during the periods of time when we needed to stop and take a rest.

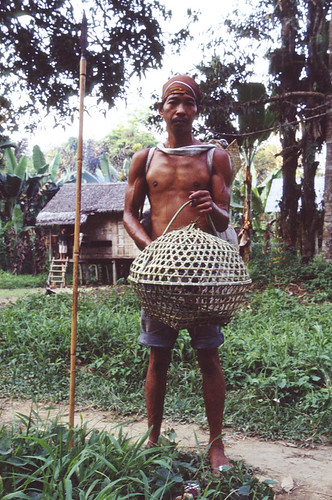

That evening we went to meet and interview a man who is known locally as Pak Harimau – Mr Tiger. This man, a small wiry 70-odd year old, claims to have killed 182 tigers over a long career of poaching. On five occasions, the tigers fought back. As his many grandchildren crowded round to listen, Pak Harimau told us the story of how the last tiger to do so dragged him 150 metres by his head. He showed us the horrific scars he bears from this encounter. Nevertheless, although he is now reformed, you get the impression that despite his age and his terrifying experiences he would resume his old career without a second thought if it became legal. He was quite a formidable character.

The last two weeks in Sumatra have been exhausting but exhilarating. We left Jakarta early one morning, accompanied by Pak Wald and Pak Daniel of the Sumatran Tiger Conservation Program, and began a four-day journey up impossibly bumpy roads to the forests of central Sumatra. En route we took in a ferry journey passing Krakatoa in the distance, stopped over at the elephant training centre in Way Kambas, and passed through the concrete skyscrapers that dominate the villages where bird’s nest soup is the primary industry. After three days circumnavigating the many potholes of the trans-Sumatran highway, we eventually arrived at the office of the STCP. That evening we were introduced to the rest of the team and were shown a small sample of the thousands of photos they have collected from their camera traps in the forests, including tapir, clouded leopards, porcupines, deer, elephants, and, of course, tigers. Pak Wald and Pak Yunus, the STCP field manager, then showed us some of the STCP’s recent confiscations – tiger and leopard skins, bones, and teeth.

The next day we traveled to some of the palm oil plantations that surround the borders of the forest where the STCP’s Tiger Protection Units run their patrols. Approaching one plantation we managed to get some shots of a huge illegal saw mill just off the road, and talked to a rubber-tapper and his family whose livelihood is threatened by the continuous expansion of palm oil monoculture. Arriving at another plantation still being established nearby, Pak Wald was shocked to find how quickly the forest had been cleared – the area had still been forest when he had last visited, just weeks earlier. On our way out of this plantation we encountered two workers carrying an Argus Pheasant that they had recently captured on the outskirts of the plantation. The Great Argus is a CITES Appendix-I listed endangered species. The unfortunate bird we met had its eyes stitched closed to “keep it calm”. The workers expected to make around £14.50 from selling it. We resisted the temptation to buy this bird from them in order to set it free – our doing so would only mean that word would get round that foreigners were paying for animals and would compound the problem.

Later, in yet another plantation, we came across a baby macaque being kept as a family pet and tethered by the neck on an extremely short rope. It is likely the macaque faces a bleak future – a macaque is almost certain to be killed by others in the group if released into a wild population. It felt like every way we turned there were animals that faced similarly uncertain futures as their forest disappears to make way for palm oil.

The next couple of days were spent more happily. We traveled to the STCP base within the forest borders and from there we were able to film siamang whooping through the treetops, and witness the spectacular site of hornbills swooshing and honking overhead. We spent a couple of days trekking the jungle trails with the team, filming the set up of the camera traps and looking for snares set by poachers. We were lucky enough to come across some tiger prints, including some left fairly recently by a tigress and her cubs.

Members of the tiger team are recruited only after rigorous jungle training, and although by now fairly acclimatized to the 33 plus degree heat, we found it hard to keep up with the speed with which they move through the forest. They decided we looked like Ninja Turtles due to the big camera cases we were heaving around on our backs, and I think that our obvious discomfort kept them entertained during the periods of time when we needed to stop and take a rest.

That evening we went to meet and interview a man who is known locally as Pak Harimau – Mr Tiger. This man, a small wiry 70-odd year old, claims to have killed 182 tigers over a long career of poaching. On five occasions, the tigers fought back. As his many grandchildren crowded round to listen, Pak Harimau told us the story of how the last tiger to do so dragged him 150 metres by his head. He showed us the horrific scars he bears from this encounter. Nevertheless, although he is now reformed, you get the impression that despite his age and his terrifying experiences he would resume his old career without a second thought if it became legal. He was quite a formidable character.